My name is Frank Gump. People call me Frank Gump. I do gotta middle name, though only Momma ever uses it, and only when she's exasperated with me: "Frank Forrester Gump!"

You’ve probably heard of my great-grandson, Forrest Gump. We Gumps have always had a knack for showing up at spots that would turn out to be historically significant. We are also magically long-lived: I was born in 1865, which makes me 146 years old now. Gumps have been Unitarians -- and now, Unitarian Universalists -- since the 1700s. It was my great-grandad (on Momma's side), Henry Ware, that caused all that stir back in 1805 when he was offered, and accepted, the Hollis Chair of Divinity at Harvard.

|

| I loved Tom Hanks as Forrest. Mr. Hanks can play me any time he wants. |

But I'm here to tell you my story, not Forrest Gump's or Forrest Church's.

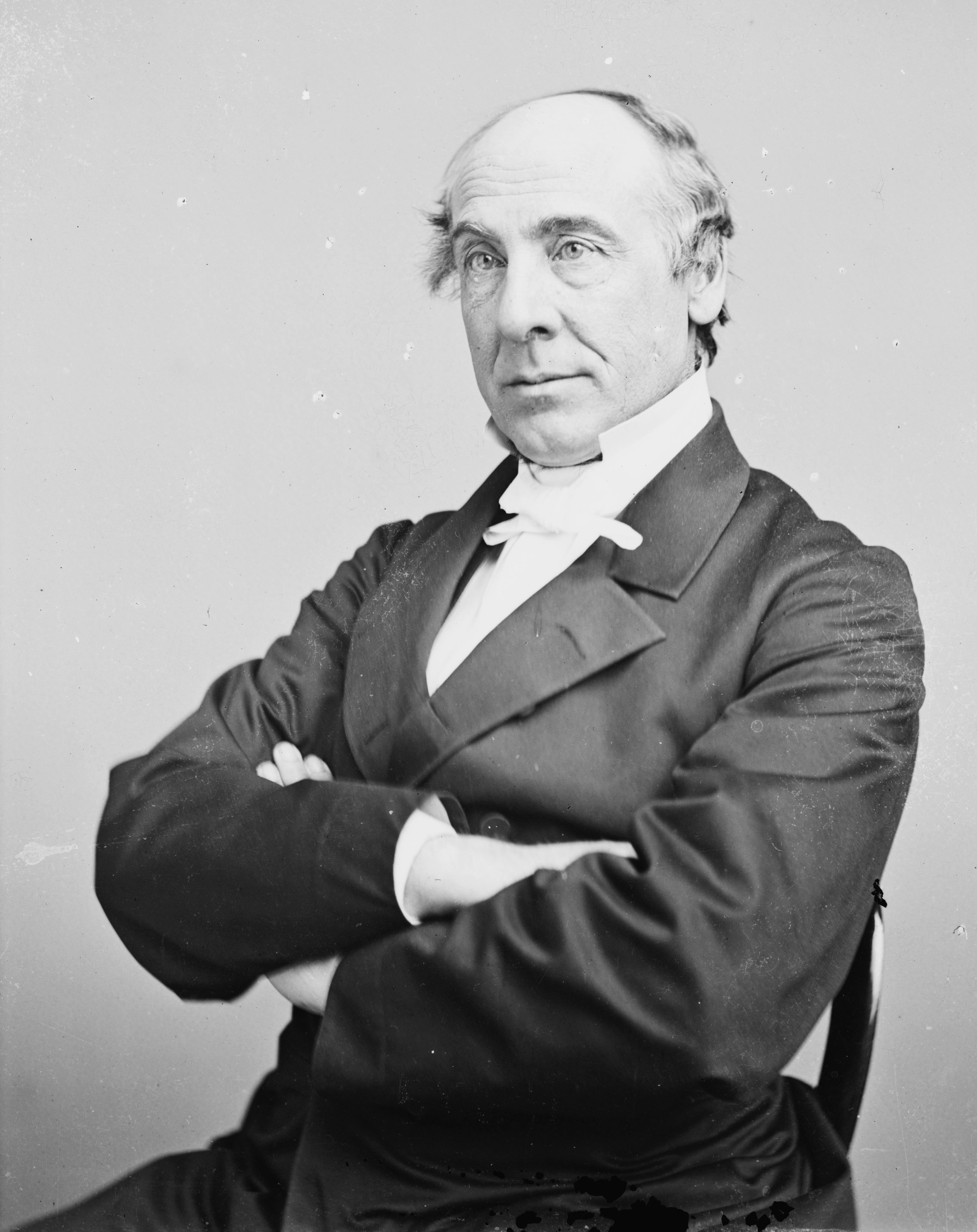

I was born in New York City because of my uncle, Rev. Henry Bellows, minister of All Souls Unitarian Church in New York. Forty years before I was to be born, in 1825, the American Unitarian Association -- AUA -- had been formed. And for forty years the AUA remained low-key and loosely organized – nothing more than a clearinghouse for a few Unitarian publications, really. It was not even an organization of congregations. AUA was an association that individuals – mostly ministers – joined.

Unitarianism was stagnating. There'd been no growth for decades. My Uncle Henry, though, was a born organizer. During the Civil War, Henry Bellows had organized the US Sanitary Commission to provide medical care to the sick and wounded soldiers. With the war over, Uncle Henry set out to whip his slack bunch of religious liberals into shape. So he organized a big conference – the first national one Unitarians had ever had.

In March 1865, he came down to visit his sister, my momma.

He said, "Come with me, Sally."

"Henry, I'm 8 months pregnant," she said.

|

| Henry Whitney Bellows 1814-1882 |

Here’s an interesting thing: the 1865 conference proposed union with the Universalists. Ha. Took us 96 more years to make that happen.

To get the word out more effectively about who we were, Uncle Henry said we needed to have a statement. Now he, like most Unitarians at that time, was a Christian. So Henry Bellows introduced a statement that said Unitarians are "disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ" devoted "to the service of God and the building-up of the kingdom of his son." That’s what it said.

Now my momma was one of the ones that weren't so sure about that. She loved to read her Ralph Waldo Emerson and the other Transcendentalists.

Henry said to her, "Sally, are you Christian?"

Momma said, "Y'know, Henry, I have to say I'm really not."

"You're not one of those radicals among us, are you?"

"Well maybe so, Henry. I been learning about Buddha, Zoroaster, and Muhammad. I'm not saying Jesus wasn't an amazing and brilliant spiritual teacher who we need to listen to and learn from, but these others had a lot going for them, too. And science is revealing whole new worlds to us. There are Unitarians now who call themselves 'scientific theists.' Henry, we've always been a noncreedal church. Trying to say we've now all got to pledge allegiance to Jesus is sectarianism. It's a violation of our principle of private judgment. I'm against it, Henry. There are some of us who have a vision for a wider world fellowship, where people with different beliefs can come together in one faith."

Henry looked confused.

Momma continued, "Yes, that's what I said: Different beliefs in one faith. Faith is so much more than just belief, Henry."

So my momma took the floor to speak against her brother's motion. "I love my brother," she said. "But I must speak frankly." She hadn't been speaking long when she said, "We don't need to affirm allegiance to Our Lord, Jesus .... Jesus ... JESUS!" She went into labor right there.

That's how I was born at the First National Unitarian Conference. She named me Frank because I was born from speaking frankly.

Despite Momma's dramatic delivery (in more senses than one), Henry Bellows' statement had majority support, and it passed. I was a toddler just 18 months old in October 1866 when I went to the second National Conference of Unitarian Churches up the road in Syracuse.

This time Uncle Henry said, "Sally, why don't you stay home?"

Momma said, "Are you kidding? I wouldn't miss it."

The radicals renewed their argument against the statement about Jesus, which they said was a creed. They tried and failed to have the statement dropped. There motion was defeated 2-1. Momma, and a bunch of others left Syracuse very disappointed.

"Frank," she said to me, lifting me into her arms, "Unitarians have removed forever the ancient principle of free inquiry, and henceforth Christianity and freedom must be irreconcilable foes. Not only that," she sighed, "but you're wet."

Momma and her friends met in Boston and organized on their own. The outcome was that in 1867, when I was two, the FRA – Free Religious Association was formed – with a purpose to:

(1) promote interests of pure religion;

(2) encourage scientific study of religion;

(3) increase fellowship of the spirit.

The FRA sought the universal element in all religion and grounded that search in a scientific approach to human nature and the external world (Schulz 16). My momma was a charter member of the Free Religious Association, but she wasn't the first one to sign the membership list. The first one to sign up was Ralph Waldo Emerson himself.

Momma and the other Unitarians kept on being Unitarians – they didn't leave that behind. But the FRA also included nonUnitarian members, and at least one Jewish rabbi.

So I grew up in the FRA, and in the Unitarian church. Through their publications and meetings, the FRA was a voice for radical religious thought – though it never established churches or developed a program. Throughout my childhood and youth, the Free Religious Association grew slowly.

Among Unitarians, the controversy around this Christian creedal statement continued. When I was 3 years old, the 1868 National Conference passed an amendment that said the statement of belief reflected the majority viewpoint, but it was nonbinding. This didn’t much satisfy the radicals, who wanted the statements of belief removed, and it ticked off the conservatives. I’ve heard the conservatives were contemplating splitting off to form their own organization, the “Evangelical Unitarian Association.” I’m glad that didn’t happen.

Now neither side was happy.When I was 5 years old, the 1870 National Conference voted overwhelmingly to reaffirm allegiance to Jesus Christ. Momma and the other radicals fumed.

|

| Octavius Brooks Frothingham 1822-1895 |

Then Rev. William Potter – also with the radicals, in fact, the secretary of the FRA -- he writes to say he does think of hisself as Unitarian, but not Christian, so he’ll leave it up to the editor to decide what to do about that.

|

| William James Potter 1829-1893 |

I was 8-9 years old while this was breaking out. “What is it, Momma?” I asked.

"Frank," she said. "Look. Octavius Brooks Frothingham can do what he likes. If he wants to not be listed, then fine. But I’m a Unitarian AND a nonchristian, and so is our minister. How dare they remove our minister and our congregation from the year-book? We’re Unitarians too, dammit."

"Momma!"

|

| Jenkin Lloyd Jones 1843-1918 |

“Well, Jenkin,” said Momma, “what are you going to do about that?”

“I'm going to encourage the spread of all varieties of liberalism and a scientifically respectable faith.”

“You do that,” said Momma.

And Jenkin Lloyd Jones did. Scientific theism grew in the Unitarian west. Meanwhile, at the national level, the year I was 17, the 1882 National Conference adopted a new article saying, again, that the statements of belief did reflect the majority view – however, those statements "are no authoritarian test of Unitarianism and are not intended to exclude from our fellowship any in general sympathy with our purposes and practical aims." That was good. All the radicals got back in the year-book.

|

| Jabez Sunderland 1842-1936 |

Is Western Unitarianism ready to give up its Christian theistic character? A united, purposive, determined group of men want to remove Unitarianism off its historic base to Free or Ethical Religion. This Western Unitarian Conference has been dangerously slipping from Unitarianism's age-old commitment to 'God and worship, to the idea of divine humanity that shines in Christ Jesus. (qtd in Schulz 17)But this time, in this place, Momma had the votes.

Instead of following Sunderland, the Western Conference moved further left and revised its statement about who it welcomed into fellowship, replacing the phrase, “all who wish to work with it in advancing the kingdom of God,” with the phrase, “all who wish to join it to help establish Truth, Righteousness, and Love in the world.”

The conservatives were stunned, and within weeks had withdrawn from the Western Unitarian Conference to form the Western Unitarian Association.

When Momma found out, she shouted, “Splitters!”

I said, “Momma, what were you doing when you formed the Free Religious Association?”

“That was different,” she said. “That wasn't just for Unitarians, and we never left our Unitarian church or its association.”

Did she have a point? I didn't argue it.

|

| William Channing Gannett 1840-1923 |

Since we moved out west and got caught up in the Western Conference, Momma hadn't been such a regular at the National or General Conferences. But Momma was slated to be a delegate to the 1894 General Conference back in Saratoga, New York. I was a 29-year-old school teacher, and our church had elected me an alternate. When Momma fell sick, I got on the train to Saratoga.

Finally, at last, a compromise was reached that was acceptable to Uncle Henry's “Broad Church” conservatives and momma's radicals. The new statement made reference to the religion of Jesus, but asserted that this religion reduced to "love of God and love to man." It emphasized our congregational polity, and cordially invited to "our fellowship any who, while differing from us in belief, are in general sympathy with our spirit and practical aims."

|

| Momma Gump |

A few days later, in a pensive mood, she said to me, "Frank, the Free Religious Association had some nonUnitarians, but I do believe its main function was to keep the Unitarians true to noncreedalism."

I said, "Momma, do you think this opens the way for the development of humanism within Unitarianism?"

She said, "Humanism? You mean like that renaissance movement?"

"Kinda, but different. Faith in science, and progress, and human reason to work out all problems, technological and social, rejection of the supernatural. You think it'll catch on?"

By 1896, ten years after it had begun, the Western Unitarian Association ceased to exist, despite the fact that they had initially had all the backing of the national body. The radical Western Unitarian Conference had prevailed.

In 1903, Momma and I took a trip down to Florida and stopped off in North Carolina for a visit with some distant relatives, the Reeses. I met my second-cousin Willi Reese. I was 38, he was 16, yet we hit it off well, despite the age and religious differences: the Reese family were devout Southern Baptists. Willi's Dad was Baptist deacon, and the Dad's father, grandfather, and two brothers were Baptist preachers. Willi and two other sons were also headed into Baptist ministry. At the age of nine, Willi had “accepted Christ as his personal savior,” and the first dollar Willi'd ever earned, he'd given to the Baptist church to help pay the minister's salary. Like I said: Religious differences. Nevertheless, Willi was bright and inquisitive and had a capacity for sympathy that resonated with me.

I marveled at Momma's restraint. After we finished our visit and were on our way, I said, “Momma, you love to argue. That stuff they said about Unitarian heresies. Why did you just let that pass.”

“Frank,” she said, “never argue with anyone who thinks the salvation of your soul depends on the outcome of the argument.”

Five years later, I was 43 and a philosophy professor at the Universalist school, Tufts University. I traveled over to Cornell to attend the 1908 American Philosophical Association meeting. It was a chance to meet colleagues and a few old friends. I was glad to see another long-time friend of the family, Frank Doan – a Unitarian minister on the faculty of Meadville Theological School – slated to give a talk at the meeting.

I'd been corresponding with Rev. Doan, and had been throwing around my word, "humanism." Doan's talk introduced his philosophy which he was calling "cosmic humanism." It was basically a liberal Christianity, but Doan always insisted upon starting with the human in his search for the divine (Schulz 19). That talk was the first time – as far as anybody's been able to tell – that a Unitarian minister used the term "humanism."

Momma was getting on in years. Convinced that Pittsburgh was ruining her health, she read that Spokane, Washington had a healthy climate, so she up and moved there.

I was 46-years-old in 1911. I took the summer off from teaching that year and boarded the train for a three-day ride to Spokane to visit Momma. On that trip, I shared a berth with a 33-year-old man named John Dietrich. Said he had been ordained a minister in the Reformed Church. They charged him with heresy. He was accused of denying the infallibility of the Bible, denying the virgin birth of Jesus, denying the deity of Jesus, and denying the efficacy of the atonement.

“Dang,” I said. “Are the accusations true?”

“Every one of them,” he said. “But are they grounds for defrocking a minister?”

“What do you think?” I asked.

“No, they aren't,” he said. “But I didn't have the stomach to fight it, and I've resigned.”

“So what's next for you?”

“I'm called to ministry, but what denomination will have me now?” he asked.

"Oh, I don't know," I said. "The Unitarians?"

|

| John Hassler Dietrich 1878-1957 |

Four and a half years later, another letter from Momma said, "Rev. Dietrich was in fine form Sunday. He announced he was adopting the term 'humanism' as a good name for his interpretation of religion in contrast to theism. Said he learned the word from a man he met on a train a few years ago."

In 1915, I celebrated my 50th birthday by accepting a job offer at the University of Minnesota. Soon, I was a member of the First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis. I'd been there scarcely a year when, in 1916, a new minister arrived: one Rev. John Dietrich, who had just completed five years in Spokane.

Dietrich was less attentive to pastoral matters than most ministers. He once told me, “Frank, in my ministry people have to have the courage to work through their personal problems by themselves.” Instead, Dietrich devoted the bulk of his time and energy to the preparation of long, meticulous sermons through which he propagated the humanist gospel (Schulz 20).

The next summer, Dietrich and I were again traveling companions. It was a shorter trip this time, as we went down to Des Moines to the 1917 annual meeting of the Western Unitarian Conference. Once there, I kept staring at our conference host, the young minister of the Des Moines Unitarian Church, about 30-years-old. He looked so familiar, but I was having a hard time placing him. Finally, it hit me. I hadn't seen him in fifteen years, and he had been just a boy then. I only dimly remembered that visit with the Southern Baptists on that North Carolina farm. And the Western Unitarian Conference was the last place I'd expect to run into:

“Cousin Willi! Is that you?”

He looked at me, startled. “I go by Curtis now,” he said. “And you are?”

|

| Curtis Reese 1887-1961 |

“There is a man you've got to meet,” I told him, and I introduced him to my minister. The two got to talking, and grew increasingly excited as they discovered that each had been exploring the idea of religion without God. Dietrich called it humanism, and Reese called it “the religion of democracy” because it did away with an autocratic ruler god. Eventually, it would be Dietrich's term that would win out. Historians now point to that meeting of two men at the Western Unitarian Conference of 1917 as the beginning of American Religious Humanism.

In the years to follow, as Dietrich and Reese preached and wrote their humanist gospel, they gained adherents and opponents. In summer 1920, Reese carried back to the stodgier East the kind of liberal thinking that was becoming common in more western churches. At the Unitarian Harvard Summer School of Theology, Reese delivered an address, “The Content of Religious Liberalism.” He said:

Historically, the basic content of religious liberalism is spiritual freedom. Out of this basic content has come the conviction of the supremacy of reason, of the primary worth of character, and of the immediate access of man to spiritual sources. Always religious liberalism has tended to replace alleged divine revelations and commands with human opinions and judgments; to develop the individual attitude in religion; and to identify righteousness with life. The method of religious liberalism has always been that of relfection, not that of authority. Liberalism has insisted on the essentially natural character of religion....The theology of Augustine and that of Channing, the theology of Billy Sunday and that of H.G. Wells, might all be found utterly inadequate without consequent injury to the religion of the liberal. Liberalism is building a religion that would not be shaken even if the thought of God were out-grown.Whoah, Nellie! Theodore Parker had argued 80 years before that the teachings of Jesus were crucial, but the person of Jesus was nonessential – in the same way that Euclid or Newton made brilliant contributions by discovering truths that anyone bright and creative and insightful enough could have discovered. For Parker, Jesus was a person like the rest of us – wiser and more compassionate, yes, but only in ways to which we, too, might aspire. Parker brought us to the religion of Jesus, not the religion about Jesus: the spiritual awareness that Jesus discovered is available to us, and we are saved neither by Jesus’ divine status nor by his cruel death, but by assiduous commitment to live as Jesus taught. Parker thought we could outgrow religion about Jesus – and that was way radical for its time. Parker had never in his wildest dreams imagined a religion in which all thought of God could be outgrown.

One periodical that covered Curtis Reese's address reported the audience reaction: "The strong were indignant and the weak wept." Indeed, the address made such an impact that religious periodicals were still referencing it six years later.

In August 1921, in Chicago, the humanist-theist controversy hit the floor of the Western Unitarian Conference. Reese, the conference organizer, invited his friend Dietrich to address the conference on “The Outlook for Religion.” Dietrich, predicted that religion would have no outlook unless it could be brought into harmony with modern thought; this meant relinquishing the idea of a divine being in control of the universe and telling humans they are the masters of their own destiny. In other words, religion had an outlook only if it became humanistic (Olds 38).

The theist opposition mustered its forces. They acknowledged that liberty was important, but they felt we must be able to assume a common faith in God among Unitarians. Though Unitarianism had remained creedless – through the work of people like Momma and her friends in the Free Religious Association – and belief in God was never formally stipulated, the theists had never expected it to be denied.

|

| William Sullivan 1872-1935 |

“What do you think is going to happen?” Dietrich asked me as he took his seat and Sullivan mounted the rostrum.

I said, “Conferences are like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're going to get.”

Sullivan believed that his own faith was traditional Unitarianism, that the church stood for something theistic, and that if one had lost this faith, then, in the name of truth, one should move elsewhere (Olds 44). Sullivan was an eloquent and powerful speaker, but he miscalculated when he ventured into personal attacks against Dietrich. We Gumps are not prone to fits of anger, but I was infuriated at the slander directed at my minister. The personal attacks backfired. The theist faction had come to the conference prepared with a resolution that the conference should formulate a Unitarian statement of faith, a kind of creed that would at least assert belief in the existence of God (Olds 44). Seeing that they did not have the delegates to win, they never submitted the resolution. What happened in Detroit was decisive, for the opportunity to pass a creedal statement about belief in God would never be greater. The controversy was not over, for at times over the ensuing years, strong feelings erupted. But as the years passed and humanists and theists worked together, they generally found the small Unitarian denomination large enough to embrace both points of view (Olds 44).

From there, humanist ideas spread within and outside Unitarian circles. In 1925, I turned 60 and celebrated another decennial birthday by changing jobs. I took a post at the University of Chicago. Three years later, 1928, a group of my students and some others organized the Humanist Fellowship and began publication of a new journal, the New Humanist. It was this group which, in 1933, produced the Humanist Manifesto. At scarcely more than 1,100 words, the Manifesto is concise and revolutionary. It's been followed by a longer "Manifesto II" of 1973 (3,626 words), and a shorter "Manifesto III" of 2003 (633 words).

The original 1933 Manifesto had 34 signatories – prominent thinkers who had involved themselves in the drafting and re-writing of the manifesto. Fifteen were Unitarian ministers; one was a Universalist minister. Several others were lay Unitarian leaders. John Dietrich and Curtis Reese, were signers.

1933 was the depression. The manifesto was an affirmation of a new hope amdist that despair.

I kept on teaching until I was 73, and when I did retire in 1938, the humanist-theist controversy pretty much retired, too. Unitarian ministers were largely agreeing that that once-heated conflict should be regarded as history. The issue continued to be discussed, more or less calmly, as we continued to process it. A very widely distributed pamphlet first published in 1954 was titled, “Why the Humanism-Theism Controversy is Out of Date.”

|

| Francis David 1510-1579 |

And just as Momma told Uncle Henry on the day I was born, "people with different beliefs can come together in one faith."

* * *

Sources:

William Schulz, Making the Manifesto: The Birth of Religious Humanism. (Skinner House, 2004)

Mason Olds, American Religious Humanism. (Fellowship of Religious Humanists, 1996).

No comments:

Post a Comment