So who are the enemies, and what does loving them mean?

LGBT folk haven’t been the enemy around Unitarian or Universalist congregations for pretty much a generation or two. Certainly, not all Unitarian Universalists are as understanding and accepting and skillful at showing it as we could be. Still, we’ve made a commitment to try. Nowadays, for us, the enemy is likely to be the people we think of as homophobic. We think they aren’t very loving. Maybe they aren’t. That’s their business. Ours is to be loving to them, whether they can ever find it in themselves to be loving to others or not.

Loving them doesn’t mean hoping they’ll change their ways, or even hoping for their own good. Loving them means the work of understanding them. Which can be difficult. Sometimes they might not understand themselves. For some of those who oppose same-sex marriage – maybe for many, maybe for most, I don’t know – it goes like this:

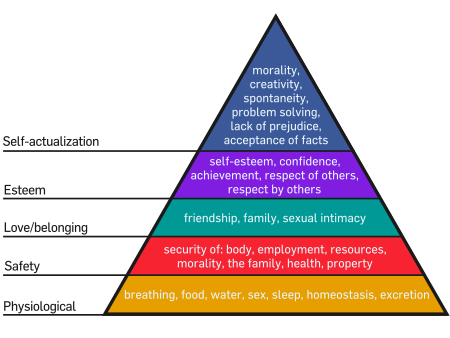

Marriage once was understood as a set of five tightly-linked features:

- creation of a household of two adults;

- sexual exclusivity to within that household;

- production of babies;

- raising of the children; and

- perpetuation of the parents’ genetic lines.

Over the course of my lifetime, those previously inextricable features of marriage have come apart -- and with that dissolution the old sexual ethic has faded. The arrival of reliable birth control meant that otherwise fertile opposite-sex couples could, as they chose, form a household together without producing or raising babies. The rise in out-of-wedlock births and single parent families has meant producing and raising children without two adults making a household together. You can have marriage without sex, and sex without marriage (which has always been fairly common but in recent decades has lost much of the stigma it used to have). You can have sex without babies, and babies without sex – the former through the aforementioned miracles of birth control, and the latter through the miracles of surrogate motherhood, artificial insemination, and adoption. You can propagate your genes without raising the children, and raise children without propagating your genes. The package deal has come undone.

It’s a little scary when what seemed like a settled, solid basic eternal verity and feature of How-Things-Are comes unglued. That’s frightening, unnerving. It’s hard to know what is solid ground anymore. I get that. I understand why there has been such resistance to same-sex marriage: it seemed to undermine the five-part package deal that marriage depended upon. (Never mind that the real unraveling of that package was already well underway from a variety of other factors.)

* * *

This is part 2 of 5 of "Just Love: Sexual Ethics Today"

Next: Part 3: "Riding Turtles Down Slippery Slopes"

Previous: Part 1: "Radical Inclusivity"