Anything that I say about being good at some things, or not so good at other things, is going to be as much about other people as it is about me. If I think I’m good at something, it’s always good compared to somebody else. If I think I’m not good at something else, it’s always not so good compared to someone else. If I assess myself smart, or intellectually inclined, or big-hearted, or hard-working, or committed -- or if I assess myself as dim, or histrionic, or disorganized -- warm or cool, old or young -- I’m equally assessing other people as being, on average, less of whatever quality, positive or negative. If I were to say I thought I was a pretty good preacher, I'd be opining just as much on the quality of my colleagues preaching as on my own.

Who am I apart from what other people are? Who am I without the judgments, with neither positive nor negative self-assessments, for judgments are always comparisons? Who am I now?

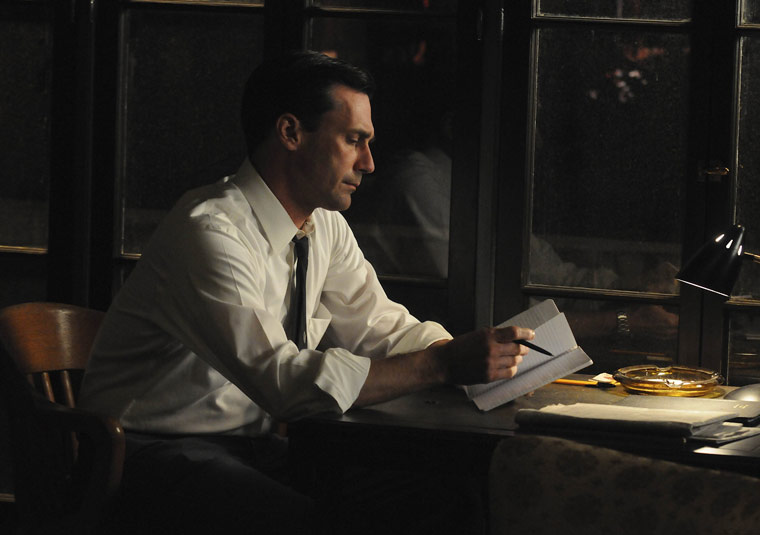

There is a story that runs along through our heads, telling us about who we are. It’s a largely unquestioned story because we don’t take it out and look at it. Fragments of the story push us this way and that. The process of journaling invites us to take it out and look at it. When we start articulating our story, we begin to make it more coherent. We fit the fragments into larger chunks. Some fragments don’t fit. This is a new discovery for us! Only then can we choose to drop the incoherent fragments so that they won't pop up to push our life one way or another anymore.

Slowly, slowly, life begins to have a greater coherence. This increasing coherence naturally happens for many of us as we age anyway. Journaling helps it happen sooner, clearer, more thoroughly.

Anne Frank, a young girl imprisoned in hiding in an attic, was able to fashion a coherence out of self and life with a pen and some bound pages. Through journaling, she brought herself into being. It was not an ordinary girl’s diary, after all. As Anne Frank wrote at the beginning:

“I want to write, but more than that, I want to bring out all kinds of things that lie buried in my heart.”What is it that lies buried in my heart? I don’t know, cannot know, what is in there until I see it manifest somewhere. Seeing it manifest on the page helps me see its manifestations elsewhere, too.

What lies buried in your heart? The journal is a life companion, always ready to help you be who you are but didn’t know it.

Life is lived, of course, day by day. The meaning of a life is the meaning of its days. Day by day we forge the chain we wear, link by link. Or, day by day, we walk an uncertain path to liberation. Or both.

Day by day.Life comes at us and flies past us day by day, or, as the French say, au jour le jour. The French jour, meaning “day,” is the root of both journey and journal. Journey originally meant one day’s work or the distance traveled in one day. And journal is the record of the day, the recording of our life's journey.

Day by day.

Oh, dear Lord,

Three things I pray:

To see thee more clearly,

Love thee more dearly,

Follow thee more nearly,

Day by day. ("Godspell")

Each fleeting day of our life, we travel one day’s distance. What did it mean? What was it for? Where did we go? Even though we were there, it is inchoate until we pull together the fragments and bind them together into a coherent accounting to ourselves.

|

| Christina Baldwin |

“Writing is sorting. Writing down the stream of consciousness gives us a way to respect the mind, to choose among and harness thoughts, to interact with and change the contents of who we think we are.” (Christina Baldwin, Life's Companion: Journal Writing as a Spiritual Quest, 9)In All the Big Questions, Rebecca Hill says:

“What is the purpose or meaning of life? To get your story straight. To create a safe and gentle environment for yourself, and help create one for other folks, for living what truth you can stand.”Without some way to do what journaling does, I will not know who I am, and will even forget that I don’t know.

“On the days when I’m not sure what the journey is or why I’m on it, I can still be sure what the journal is and why I write. I can hold onto my journal, write in it, lament and question and celebrate. . . . The format changes, the pens change, the contents vary, the cast of characters comes and goes. Yet this tangible object reminds me that my life is being lived on many levels, it reminds me that I need to act, watch, reflect, write, and then act more clearly. It urges me to remember to pay attention to spirit,” (Baldwin 11)to the impulses and intuitions that may not be getting things exactly right but that nevertheless have a source in something important.

Sometimes I want to say that it feels like finally taking charge of my own life, finally defining for myself who I am, weeding out the impulse fragments that do not cohere. Or I want to say just the opposite: that it feels like letting go of the illusion of control. Life knows better plans than I can imagine. Much of what I write is to recognize where my clinging is. Recognizing makes possible releasing.

Whether it feels more like taking charge or more like letting go, over time, the repeated noticing of the conversation the mind is having with itself begins to change that conversation.

“One of the greatest powers of journal writing is that over time it helps us notice, influence, and change the conversation the mind is having with itself. This dialogue is nearly constant. All I'm suggesting is that some of it, especially that which is directed to specific questions, is extremely helpful to write down.” (Baldwin 27)The journal writer’s mission is reclamation:

“to reclaim a sense of place, a sense of empowerment, a sense of healthy relationship between our lives and times.” (15)I called the journal a companion, for there is a sense of conversation, of dialog, in journaling. It’s common for journalers to give their journal a name, and write entries addressed to the imaginary personage. Anne Frank called hers Kitty.

“Spiritual writing expands the interior conversation of consciousness to include your relationship with the sacred. You are no longer alone on the quest, or on paper. You are in conversation with Something you perceive as beyond, or deep within, yourself.” (23)There is no map anyone can hand you for your spiritual journey. So you must make your map as you go. As Ponce de Leon, we are voyagers into a new world. As he explored this land we call Florida, having no idea of its coastline, let alone its interiors, he mapped as he went. So must we.

The map we make as we go is a rough sketch of where we have been with maybe some even rougher indications of what may lie ahead, gathered from unreliable scouting reports. Since it shows only the path we’ve traveled, not the surrounding area, not the destination, or possible routes to get there, it doesn’t do much of what we want a good map to do for us. Nevertheless, the map we make as we go is essential in trekking this unchartered wilderness called life. Only with careful attention to where we have been, laying out the experiences of the day so as to clarify their spatial relation to one another, will we be able to recognize, and thus avoid, going in circles. Our journal is our map of where we have been on our spiritual journey – a sketch of the terrain covered during each day, sometimes with some guesses about what may be ahead. Without it, I go in circles and do not even realize that I am.

It is a terrain of questions: questions to explore rather than to answer, to savor rather than resolve. As writer Ingrid Bengis says,

“The real questions are the ones that obtrude upon you consciousness whether you like or not, the ones that make your mind start vibrating like a jackhammer, the ones that you ‘come to terms with’ only to discover that they are still there. The real questions refuse to be placated. They barge into your life at times when it seems most important for them to stay away. They are the questions asked most frequently and answered most inadequately, the ones that reveal their true natures slowly, reluctantly, and most often against your will.”Questions propel the spiritual quest and mapping them fills the pages. You might sometimes take a journal entry just to list questions you have, big and little:

“What’s for dinner? Who am I? What am I supposed to be doing with my life now? Who am I supposed to be doing it with? Will I have fun? What is the nature of spiritual fun? Will I recognize it when it happens? Is there a God out there, or is God all in here? Is God laughing at all the silly questions I ask? Are these silly questions? Is there life on other planets? Do they care about life on this one? Do I care about life on this one? What would I be willing to give up to save the world? What are life’s real essentials for me?” (36)

“The comfort that comes from questioning is this: even if there isn’t an answer, there is response. There is a sense of the sacred reaching toward us, as we reach toward it. . . . The voice of the sacred appears gently on the page, written in our own handwriting but carrying a message of support and comfort, sometimes challenge, which we do not generate alone” (39)– at least, the conscious part of us does not generate it alone.

Open the covers, lay the page before you. The soul whispers vieni spirito creatore: come creative spirit. Be with me on this quest to create meaning from the flotsam and jetsam of this, the shipwreck of my life.

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, instructs:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves. . . . Do not now seek the answers which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them and the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”I like that. I neither find the answer nor have the answer nor know the answer. Rather, I live into my answer -- if, that is, I first put in the time living the question.

Nuts and Bolts

If you are just getting started, your question is: "How do I journal?"

There are two rules.

- Rule #1: date your entries as you go.

- Rule #2: don’t make any other rules.

The spirit listeth where it will. Try to get out of its way and let it. Spirit, however, sometimes requires some coaxing to speak up. You must decide upon a discipline. You can change it as you feel the need – yet creative freedom thrives best within a clear framework.

Here are five journaling exercises.

First exercise: timed entries.

Set a timer for 5-7 minutes, and write until the timer goes off. Stop writing when the time is up, even in the middle of a sentence. Close the journal and put it away until the next day. This primes the creative pump, helps give you a sense having more to write than you have yet written.

“The frustration of stopping creates the impetus to write more. You become more interested in the ideas and thoughts you want to put down,” (25)more eager to get back to the journal. “A week of timed writing will sharpen your writing focus” (25).

Second exercise: flow writing.

“Pick a tangible object from your surroundings and use it as the opening image in your entry. Let your mind free-associate from one thought to the next.” (24)You can go until you have arrived at a place that feels finished, or you can combine these two exercises, and make this a timed entry. You’re writing the stream of consciousness, “learning to trust that no matter where you start, words will come to you” (25).

Flow writing rides the surface of the stream, rather than diving deep. It glances among tips of icebergs, “touching on thoughts that ride deeply. You can expand the ideas that interest you at a later time.”

Third exercise: Dialog writing.

First, write a question at the top of the page. Take a breath, pause, listen. Write down the first response that comes. Ask follow-up questions, so as to create a rhythm of question-answer, a sense of back-and-forth dialog. Trust yourself to play both roles, to write in multiple voices. If you feel stuck and don’t know where to go next, bring in a third voice – an “overvoice” observer “that comments on how the dialog is developing and helps you see where it needs to go” (26).

“For example, if every time you talk to your exspouse, the two of you reach an impasse, don’t faithfully recite your exact words when you dialog about this situation, but drop beneath the verbal exchange. Ask yourself and ask the other with whom you write: Why do we get stuck at this point? What do you think is going on? How do you suppose we could get beyond this point? What are you willing to do? Here's what I'm willing to do. The more specific the quetion, the more specific the response will be. Dialoguin is such an imporatnt journal-writing tool, it will show up in many variation. Whenever you get stuck in your monolog, open your mind to dialog. You will be amazed at the insight waiting for you to ask instead of tell” (29).

Fourth exercise: Unsent letters.

Most of the time in journaling it is important that your only audience is yourself. If you are thinking that someday your journals will be discovered and published, or read by your descendants, then you begin to self-censor, to tailor yourself to your audience, to push aside the impulses that won’t make sense to them. Journaling is for your eyes only. So even when you imaginatively address yourself to a particular other person, be clear with yourself that this is to be an unsent letter. For your first foray, it might help to address a letter that cannot be sent: address it to yourself as a child, or to a child you never had, or to a fictional character in a novel you love, or to someone you knew who has died.

“The purpose of the unsent letter is to discover what impetus motivated it – which you may not know at the beginning – and decide what you need to do next, having discovered that impetus” (31).The unsent letter may bring closure to an unresolved area of life – or it may bring new opening to a closed area.

Fifth: gratitude journaling.

I really recommend doing this one once a week. Do something else the other six days, and once a week, simply list things for the last week that you are grateful for. Nurturing the attitude of gratitude moistens the soil from which everything else green and joyful can grow. Please see the New York Times article yesterday (2011 Nov 21) on the value and power of gratitude: click here.

Conclusion

We might think of journaling as the keeping of a ship’s log. Note where you are, or you will be lost at sea.

Come to the edge of the ship's deck.

Through the telescope of the page, gaze out in wonder.

Cast your questions into the deep.

The wide universe is the ocean we travel.Amen.

And the earth is our blue boat home. (Peter Mayer, "Blue Boat Home")