|

| Worcester Union Station |

And what are we supposed to do with it?

Jack Kerouac’s novel, On the Road, thinly fictionalizes his travel adventures across late-1940s America. I was, in a milder, tamer way, on the road myself this last week. Most of the way was by plane -- I flew from Gainesville to Atlanta, then Atlanta to Boston. And the train I hopped, from Boston out to Worcester, Massachusetts, I had a legitimate ticket for. The train arrived in Worcester shortly after midnight, so I did have the chance to feel rather beatnik-hobo as I hoofed it three miles in the middle of the night from Worcester Union Station to the retreat center where I spent the week. (For more on that, click here.) Yes, there was a line of cabs at the station, and, sure, I had plenty of cash on hand to take one. But that didn't feel very adventurous. Or like much of a way to look for America along a three-mile stretch of Pleasant Street, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Besides, I'm cheap. And could always use a little exercise.

After the retreat was over, I was on the train back to Boston. The conductor came by to sell me my ticket and noticed the book I was reading. This is either the advantage, or the disadvantage, depending on how you look at it, of deciding not to get On the Road on my Kindle.

"Kerouac," he said. "I dated his niece once."

"Oh, yeah?" I said. "What was her name?"

He thought a moment. "Colette."

"Wow. Was she a Kerouac?"

"No, no. It was her mother that was Jack's sister," explained the conductor as he handed me my change. Then he he was gone on down the aisle. I returned to my book. The train, and Kerouac's prose, rambled on.

When I got home I did some googling around. Jack Kerouac only had one sister, Caroline. And Caroline had one child, a son. No daughter. Maybe the conductor had meant a grandniece of a cousin of Kerouac or something. Or maybe he made it up entirely. Perhaps some part of his brain was remembering something Jackie Kennedy said shortly after JFK was elected in 1960: "I read everything from Colette to Kerouac." In any case, there's something about this Beatnik literary figure that people want to feel close to, somehow, in some way.

Kerouac struggled with what he wanted this book to be for several years. Then, in April 1951, in a three-week burst, staying awake with Benzedrine, he wrote almost without pause. He didn’t even want to pause to change sheets of paper in his typewriter. So he cut tracing paper sheets to size and taped them together into one long hundred and twenty-foot scroll. And the thing flowed out of him, single-spaced, without margins or paragraph breaks. That was the first draft. Then there were six years of looking for a publisher and working with editors, and revising. (Previous blog entry has excerpts, and video of Kerouac reading from On the Road and Visions of Cody: click here).

The original scroll of the first draft is now a revered artifact of American letters. In the picture, you see it stretched out like a road – a road of words, without even a paragraph break crack in its pavement, a road that beckons to us on that journey: journey to where?

Where does Kerouac’s road want to take us? Kerouac’s quest is religious. For him as for the beat generation generally, the journey is a spiritual one. The real road is the inward one, the road to find ourselves, to find authenticity.

What are we, really? And can we really be our true selves? In On the Road, Jack Kerouac gives himself the name Sal Paradise, and he chronicles his road trips back and forth across the United States – to find Dean Moriarty, to go away from him, to go back to him. Three different around-the-country trips are chronicled: one in 1947, one in 1949, and one in 1950. In between the first and the second one, Kerouac wrote in his journal:

In America today there’s a claw hanging over our brains, which must be pushed aside else it will clutch and strangle our real selves.Our real selves. Our real selves?

On his first trip westward Sal and someone he’s just met are hitchhiking together.

A tall, lanky fellow in a gallon hat stopped his car on the wrong side of the road and came over to us; he looked like a sheriff. We prepared our stories secretly. He took his time coming over.

"You boys going to get somewhere, or just going?"

We didn’t understand his question, and it was a damned good question.

|

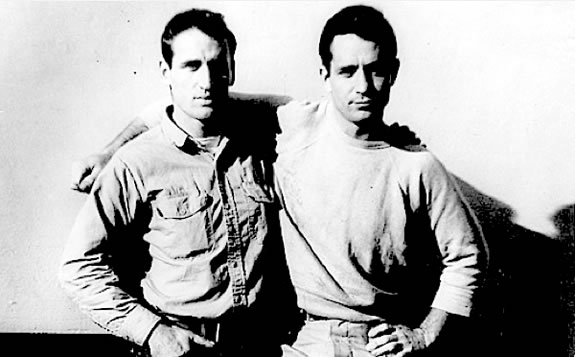

| Cassady, left, and Kerouac |

In that quest, the idea of Dean Moriarty haunts Sal Paradise/Jack Kerouac: "I think of Dean Moriarty," is the last sentence of the book. This Dean Moriarty represents wildness, liberation, freedom, vitality. Moriarty – in real life Neal Cassady – actually was born on the road, “when his parents were passing through Salt Lake City, Utah in 1926” (On the Road, 3). Mother died when he was 10; raised by his alcoholic tinsmith father in Denver; much of his youth lived on the streets of skid row with his father, or in reform school for various thefts. Stealing cars was an early talent and habit. At 19, out of jail, he and first wife “Marylou” – the real life Luanne Henderson – moved to New York, where he and Kerouac met.

Moriarty/Cassady’s powerful enthusiasm, unconstrained by law or convention, his insatiable sexuality, and wildness attracts Kerouac, though Kerouac himself doesn’t go there. He thinks that maybe he would like to, but Kerouac ultimately has other loyalties, to family and stability.

Life on the road is unpredictable, wild, moment-to-moment. There are times when the money runs out, even for food, and hunger becomes very real. There are also times of reading poetry aloud, and all-night long intense and earnest discussions. And other nights in smoky jazz clubs saying things like “man that cat can blow.” And sex and drugs with a variety of partners and substances. There are moments of ecstasy, and also sadness. At one point Kerouac writes:

As the river poured down from mid-America by starlight I knew,

I knew like mad that everything I had ever known and would ever know was One. (147)

|

| from the upcoming film, On the Road |

And for just a moment I had reached the point of ecstasy that I always wanted to reach, which was the complete step across chronological time into timeless shadows, and wonderment in the bleakness of the mortal realm, and the sensation of death kicking at my heels to move on, with a phantom dogging its own heels, and myself hurrying to a plank where all the angels dove off and flew into the holy void of uncreated emptiness, the potent and inconceivable radiancies shining in bright Mind Essence, innumerable lotus-lands falling open in the magic mothswarm of heaven. . . . I realized it was only because of the stability of the intrinsic Mind that these ripples of birth and death took place. (173)These moments come along with a lot of sadness – whether it’s the “feeling of sadness that only bus stations have” (35) -- or the sadness of failing to live the holiness and preciousness of every moment:

We lay on our backs, looking at the ceiling and wondering what God had wrought when He made life so sad. . . . Boys and girls in America have such a sad time together; sophistication demands that they submit to sex immediately without proper preliminary talk. Not courting talk – real straight talk about souls, for life is holy and every moment is precious. (57)Dean represents for Sal a kind of sacred insanity, a spiritual visionary. About two-thirds through the book, after Sal and Dean have been apart for a year, Sal hits the road again, looking for Dean. When he finds him, Dean is falling apart – but still shining a kind of light. Here’s Dean Moriarty speaking of himself in third person:

I’m classification three-A, jazz-hounded Moriarty has a sore butt, his wife gives him daily injections of penicillin for his thumb, which produces hives, for he’s allergic. He must take sixty thousand units of Fleming’s juice within a month. He must take one tablet every four hours for this month to combat allergy produced from his juice. He must take codeine aspirin to relieve the pain in his thumb. He must have surgery on his leg for an inflamed cyst. He must rise next Monday at six a.m. to get his teeth cleaned. He must see a foot doctor twice a week for treatment. He must take cough syrup each night. He must blow and snort constantly to clear his nose, which has collapsed just under the bridge where an operation some years ago weakened it. He lost his thumb on his throwing arm. Greatest seventy-yard passer in the history of New Mexico State Reformatory. And yet – and yet, I’ve never felt better and finer and happier with the world and to see little lovely children playing in the sun and I am so glad to see you, my fine gone wonderful Sal, and I know, I know everything will be all right. (185-86)

In real life, this Neal Cassady, with his crazy intensity of life, unstoppable energy, overwhelming charm, and savvy hustle, did only a little writing: published some poems and an autobiographical novel. Mostly, however, Neal Cassady was an artist whose medium was being. The pen, really, was too slow for him: Cassady was a live show. He was a muse, an inspiration, for Kerouac, for Allen Ginsberg, who writes about Cassady in “Howl,” the most famous Beat poem, which calls “N.C.” (Neal Cassady) the "secret hero of these poems."

In real life, this Neal Cassady, with his crazy intensity of life, unstoppable energy, overwhelming charm, and savvy hustle, did only a little writing: published some poems and an autobiographical novel. Mostly, however, Neal Cassady was an artist whose medium was being. The pen, really, was too slow for him: Cassady was a live show. He was a muse, an inspiration, for Kerouac, for Allen Ginsberg, who writes about Cassady in “Howl,” the most famous Beat poem, which calls “N.C.” (Neal Cassady) the "secret hero of these poems."Cassady would go on to meet Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1962, and became one of the Merry Pranksters, a group that formed around Kesey. Kesey wrote about Cassady in the book Demon Box, calling him “Superman.” In 1964, Cassady was the main bus driver of a bus – the destination across its front simply saying, “Further” -- immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Hunter S. Thompson wrote about him in his book, Hell’s Angels.

Who was this guy, irresistible to writers as he was also to a great many women – and more than a few men – with whom he slept? What kind of model of life is this?

In one scene from On the Road, Neal/Dean, with his body seemingly falling apart, is thrown out by his wife, and his primary recurrent girlfriend, formerly also his wife, leaves him. Dean and Sal go looking for sleeping accommodations at another friend’s place, Ed Dunkel. Ed himself has disappeared for a while on the road, and Ed’s wife, Galatea, lets them in and several of the women cohorts of the male Beat characters are there and take the opportunity to express their collective condemnation:

“For years now you haven’t had any sense of responsibility for anyone. You’ve done so many awful things I don’t know what to say to you.”Suddenly we see that this familiar, familiar voice of morality and reason, source of so much rage, is as filled with contradictions as Dean’s free-wheeling is. If you were any good you’d go back, but don’t you go back because she won’t have you. And the people we want are the ones we want to kill.

And in fact that was the point, and they all sat around looking at Dean with lowered and hating eyes, and he stood on the carpet in the middle of them and giggled – he just giggled. He made a little dance. . . .

I suddenly realized that Dean, by virtue of his enormous series of sins, was becoming the Idiot, the Imbecile, the Saint of the lot.

“You have absolutely no regard for anybody but yourself and your damned kicks. All you think about is . . . how much money or fun you can get out of people and then you just throw them aside. Not only that but you’re silly about it. It never occurs to you that life is serious and there are people trying to make something decent out of it instead of just goofing all the time.”

That’s what Dean was, the HOLY GOOF.

“You stand here and make silly faces, and I don’t think there’s a care in your heart.” [said Galatea]

This was not true; I knew better and I could have told them all. I didn’t see any sense in trying it. I longed to go and put my arm around Dean and say, Now look here, all of you, remember just one thing: this guy has his troubles too, and another thing, he never complains

and he’s given all of you a damned good time just being himself, and if that isn’t enough for you then send him to the firing squad, that’s apparently what you’re itching to do anyway. . . .

“Now you’re going East with Sal,” Galatea said, “and what do you think you’re going to accomplish by that? Camille has to stay home and mind the baby now you’re gone – how can she keep her job? – and she never wants to see you again and I don’t blame her. If you see Ed along the road you tell him to come back to me or I’ll kill him.”

Where once Dean would have talked his way out, he now fell silent himself,Does Dean Moriarty Neal Cassady have the secret? Doesn’t he?

but standing in front of everybody, ragged and broken and idiotic, right under the lightbulbs, his boney mad face covered with sweat and throbbing veins, saying, ‘yes, yes, yes,’ as though tremendous revelations were pouring into him all the time now, and I am convinced they were, and the others suspected as much and were frightened. He was BEAT – the root, the soul of Beatific. . . .

There was a strange sense of maternal satisfaction in the air, for the girls were really looking at Dean the way a mother looks at the dearest and most errant child, and he with his sad thumb and all his revelations knew it well, and that was why he was able, in tick-tocking silence, to walk out of the apartment without a word, to wait for us downstairs as soon as we’d made up our minds about time.

This was what we sensed about the ghost on the sidewalk. I looked out the window. He was alone in the doorway, digging the street. Bitterness, recriminations, advice, morality, sadness – everything was behind him, and ahead of him was the ragged and ecstatic joy of pure being.

“Come on, Galatea, Marie, let’s go hit the jazz joints and forget it. Dean will be dead someday. Then what can you say to him?”

“The sooner he’s dead the better,” said Galatea, and she spoke officially for almost everyone in the room.

“Very well, then,” I said, “but now he’s alive, and I’ll bet you want to know what he does next, and that’s because he’s got the secret that we’re all busting to find,” (195)

Does he?

Ah, what is this life?

And what are we supposed to do with it?

Neal/Dean is a heroic figure in that he attempts to live a life beyond the time-bound compromises most of us make with life. But he’s also a sad and tragic figure in that this very same uncompromising stance ultimately leaves him abandoned. (Edington, The Beat Face of God, 100)At the end of On the Road, Sal drives off with friends leaving Dean alone in the cold.

Conventional morality says: Choose between living for yourself and caring about others. Or try somehow to hew a balance between these opposites. Conventional morality is surely wrong. Living for yourself and caring about others are not opposites. The greatest gift that you can give this world is the gift of presenting to it who you truly are – your most real and authentic self, following no script, creatively present to each moment, ready to surprise and be surprised. And that very thing is also your own deepest desire.

I don’t know what to tell you about how to address the challenge presented to us in the figure of Dean Moriarity/Neal Cassady. After all, the point is that my guidance is beside the point. Don’t listen to the preachers – even if they dress in black and look scruffy. Listen to yourself.

Ironically maybe, listen to himself is what Dean Moriarty fails to do. Impulses pour out of him, but is he even aware of them at any point before he is in the middle of what they compel him to do? He doesn’t so much have impulses as the impulses have him. Is that freedom? Is that calmly greeting the tiger of fear with a steadfast “hello, tiger,” presence? Or, instead of fleeing from the tiger into conformity and conventional morality, does Dean merely flee the opposite direction into excess?

I believe that your true self emerges from neither repressing nor indulging. Attend to the impulses, the mad, wild desires. Don’t push them down or away; they are always offering you a teaching: listen carefully.

Listen always. Indulge sometimes.

Follow no formula, but a creative and loving and spontaneous wisdom.

This is no easy thing to do. It is the vaguely defined destination of my own life’s road trip, the "Further" to which I imagine my bus is headed, the damned good question I don’t understand. I do believe, though, that listening to what is going on in us requires cultivating a stillness and silence, so we can hear – and that’s something Dean Moriarty could never sit still long enough to do. Kerouac writes:

With frantic Dean I was rushing through the world without a chance to see it. (205)Yeah, man.

Slow down.

Slow down and maybe then see what this life is.

And what to do with it? You could take it on the road every once in a while.

No comments:

Post a Comment