A Natural History of Compassion

The news is good. Compassion emerged from the faith instinct, and it has been evolving, growing, and spreading. We are getting better able to be caring toward strangers -- not just our own families and tribes. That's good news indeed!

It's just that progress is very . . . very . . . slow.

We'll begin with some suggestive anthropological findings about early humans, and then look at how compassion and hospitality develop in literary, including Biblical, history.

The Inhospitable Early Humans: The Roots of Religion in the Needs of War

When our ancestors were hunter-gathers, as hominids have been for the vast majority of their history, war was small-scale and frequent. Bands of males attacked other bands of males – as chimpanzees do today. Nicholas Wade writes:

Chimpanzees in fact occupy territories that are patrolled and defended by bands of males. Through raids and ambushes, they try to pick off the males of a neighboring group one by one until they are able to annex the group’s territory and females. (Wade 48)Among early humans,

About 75 percent [of pre-state societies] went to war at least once every 2 years . . . whereas the modern nation state goes to war about once a generation.Enslavement was not practiced, and prisoners were not taken:

Captured warriors were killed on the spot. Anthropologist Lawrence Keeley estimates that a typical tribal society lost about 0.5 of its population in combat each year, far more than the toll suffered by most modern states. (Wade 49)Another study estimates that 13-15 percent of all deaths among foragers were due to warfare. Compare that to

the percentage of deaths due to warfare in the United States and Europe during the twentieth century, the epoch of two world wars: less than 1 percent of male deaths. (Samuel Bowles cited by Wade 72)Why do we do this? Why have humans and pre-humans been fighting and killing each other for millions of years?

It seems to be what social animals do. A group that is able to work together enhances the spread of its genes by working together to conquer neighbors. Ants, for example,

are territorial and will fight pitched battles at their borders with neighboring groups.Human groups face a constant tension: commitment and sacrifice may be good for the group, but bad for individuals. A situation in which every one else was courageous and took risks to protect the group, while I could stay back, avoid the risks of fighting while reaping the benefits of keeping rival groups at bay, would be ideal for my genes. But if everyone follows that strategy, the group will be undefended -- and short-lived. So human groups put a lot of energy into keeping freeloading low and group commitment high: we monitor, condemn, and punish those who don’t do their part. Survival depended on it.

Small groups used gossip to keep people in line, but once a group gets past about 150 people, there are too many for gossip to keep up with. We needed another strategy.

Rituals and shared music, dancing and drumming, helped our ancestors rev up certain neuropeptides and hormones and neural pathways of group connectedness. We felt much more connected to the group. Public ritual and ceremony also allowed monitoring who wasn’t participating -- and therefore who wasn’t so reliably connected to the group.

Moreover, our sociable brains, highly attuned to other people – who to approve and disapprove of, and who is approving and disapproving of us – are primed to see the same thing in the natural world: that the sky and earth, too, are monitoring us with approval and disapproval. We used shared story-telling to reinforce the sense of person-like monitors, judges – and sometimes guides – in earth, sky, sun, moon, rivers, mountains, animals.

Religion, which comes from the latin, religare, meaning to bind together, really does bind us together – in the sharing of rituals, ceremonies, music, dance, and sacred stories. Religion exists in every human culture because it is so good as a functional adaptation to bind our group together so we can compete successfully against other groups.

Religion Transcends Its Origins

But then a funny thing happened on the way to the forum. Religion started getting out of control. Not that it was ever exactly in anybody’s control. I mean, the faith instinct started spreading beyond its purpose. Slowly, slowly, the connection we had to our tribe also connected us to people outside our tribe, even to our enemies. For several millennia, there were only isolated outbreaks of compassion for the stranger. In a recognition of shared pain our circuitry of connection is sometimes sparked – if we let it be.

Homer’s Iliad, for instance, tells how the Trojan Hector killed the Greek, Patroclus, Achilles’ dearest friend. Achilles, mad with rage, finds a way to isolate Hector in battle, kills him, mutilates the body, refuses to give it to the family for burial, which means Hector’s soul will never know rest. What happened next, Karen Armstrong, in a lecture I heard her give at General Assembly last month, described this way:

But then one night Hector's father, old King Priam of Troy, comes into enemy territory into the Greek camp in disguise, and he makes his way to Achilles' tent, and he takes off his disguise and everybody, of course, is shocked. The old, old man comes forward and pulls at Achilles feet to plead for the body of his son. He embraces Achilles' knees and he weeps.(See the video and transcript of Karen Armstrong's Ware Lecture: click here)

At this point, Homer calls Achilles manslaughtering Achilles. Achilles has killed not only Hector, but many other of Priam's sons. Achilles looks at the old man and he thinks of his own father and he, too, begins to weep. The two men weep together out of their private pain, but creating a bond, that bond between people. Priam weeps for all of his sons. Achilles weeps, Homer says, now for his father, now for Petroclus. Then the weeping stops, and Achilles goes for Hector's body. He carries it and lays it very gently and tenderly in the arms of the old man, afraid that this will be too much for the old man to bear. The two men look at each other and each recognizes the other as divine. It's when we can go beyond the hatred, the enmity that knocks us into so much grief and pain and violence, it's then that we become god like. That is the end of the religious quest.

Tomorrow they will be trying to kill each other again. For a moment, the recognition of shared pain creates compassion – literally with-feeling – com = "with," passion = "feeling." In feeling with each other, they have a moment of that experience of connection, the kind of connection we were made for, the kind in which we become god-like because everything that the word God was ever supposed to mean – all the depth of sincerest devotion and the awe of infinite mystery and love – is right there.

In Homer, we find this moment of recognition of shared pain. In Genesis there's a story of hospitality that seems to come less from a particular great pain, and merely from the recognition that compassion to strangers is called for. It is, in fact, the way that we encounter the holy.

Hospitality: The Call to Compassion Outside Ourselves, Our Family, Our Tribe

Genesis, chapter 18:

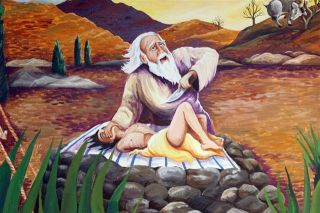

The Lord appeared to Abraham by the oaks of Mamre, as he sat at the entrance of his tent in the heat of the day. He looked up and saw three men standing near him. When he saw them, he ran from the tent entrance to meet them, and bowed down to the ground. He said, “My lord, if I find favor with you, do not pass by your servant.”Now Abraham doesn’t recognize who these visitors are. Abraham's use of “my lord,” is a general term of respect. His running out to meet them and bowing down are the same generous hospitality he might show any human visitor. Abraham continues:

"Let a little water be brought, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree. Let me bring a little bread, that you may refesh yourselves, and after that you may pass on – since you have come to your servant.” So they said, “Do as you have said.”It was a patriarchal culture, so when Abraham decides to have guests, Sarah has to get to work – though Abraham is busy, too:

And Abraham hastened into the tent to Sarah, and said, “Make ready quickly three measures of choice flour, knead it, and make cakes.” Abraham ran to the heard, and took a calf, tender and good, and gave it to the servant, who hastened to prepare it. Then he took curds and milk and the calf that he had prepared, and set it before them; and he stood by them under the tree while they ate.(For Rev. Kaaren Anderson's General Assembly Worship sermon which inspired me to delve into this Abraham story, click here.)

In ancient times, a stranger often represented a threat. Yet Abraham rushes out to show kindness. He sets out his best offering. What he finds out, is that he is serving God. Abraham's act of practical compassion leads to a holy encounter.

There.

That’s it.

As I read that story, it’s not that reaching out to needs greater than our own causes a magical being to reward us for it – though I understand why a group might describe it that way. It certainly feels magical. Reaching out and connecting is the holy encounter. We touch the divine when we contact in compassion the other, the stranger. Whoever it is, that’s God.

A man I know who has worked for three years to help the homeless here in Gainesville spoke to me one day of how in the preceding couple months, something switched in him. He was not a man who thought about or believed God – words like holy, sacred, divine, transcendent were not in his vocabulary.Yet all of a sudden, as he was downtown distributing toiletries and socks, he began to have a new sensation. He didn’t know what word to use for it except “holy or something.” In the homeless men and women he saw shining beings, whose light made him shining too.

Connecting in compassion is the holy encounter, and the Biblical story of Abraham's hospitality teaches us that.

Abraham and Isaac: Other means Other

Now, if you are thinking about Abraham, you might also be remembering another Abraham story. You might be thinking that old Abraham doesn’t seem very compassionate a few years later as he prepares to sacrifice his son Isaac.

What do you make of that episode? If a man today said that God told him to kill his son, and he was preparing to do it, we’d call protective services, no question. Yet the story tells us that there is a meaning and a joy in a connection that isn’t just about you and your interests and your family.

The call of the divine is the call to hospitality outside the usual circle of loyalty, compassion to the stranger, a connection that stretches us. That’s where we encounter the holy. The point was made in the story about Abraham meeting God by being hospitable to three strangers. Then the point is driven home by the story of the binding of Isaac. The Isaac story is saying: if you think that just taking care of your own is where it’s at, you’ve missed it. Other means really other. Abraham’s willingness to cut off his own line, his greatest interest, represents in parable the dethroning of himself from the center of the world – a giving himself over to something bigger than himself – a connectedness beyond his own (his family's, his tribe's) interests.

Modern listeners can't help but think about Isaac's interests. But remember that for the peoples of the Ancient Near East, children had no interests of their own -- they were solely a part of their father's interests. Thus, the crucial part of the story is Abraham's willingness to give up himself. Isaac represents Abraham's last chance at the sort of immortality that progeny provide, for Ishmael had been sent away. Abraham stands ready to die without any "living on" in a son. He is ready to die utterly. For it is not Self that life is for; it is Other, represented here by God, the Holy Wholly Other.

Every religion still has tribal forms – forms that celebrate “us” through demonizing “them.” And all the major world religions also have universal forms -- forms that recognize that “us” means all beings. To this day, we see all around us the playing out of this tension between tribal religion and universal religion.

I am inspired by the lesson of hospitality in the Abraham story. I am also inspired by what we now know of how the story itself originated. We now turn to the story of the story: the conditions under which the Abrahamic legend was created.

Exile Begat Abraham

The setting of the Abraham stories (Genesis 11 to 25) is somewhere around the 18th century BCE. Those stories were created, according to a growing consensus of scholars, in the 6th century BCE, during the period of exile known as the Babylonian Captivity. The Babylonians conquered Judah, and the Israelites were enslaved and taken far away to Babylon. The 70-year period of Babylonian exile, until Babylon in turn fell to Persia and some, at least, of the Hebrews returned to their land, was a period of deep reflection on the meaning of who they were and why their God had abandoned them.

During the exile, the stories about King David that are in the Biblical books of Samuel and Kings were compiled, incorporating earlier fragments. Some kind of David probably really existed and lived around 1000 BCE. Some scholars think the story in Samuel and Kings is roughly historically accurate. Extensive archaeological excavations, however, show that the City of David -- the original urban core of Jerusalem where the Bible says David and Solomon ruled -- was not a significant population center in the 10th century BCE. Parts of Samuel characterize David as a charismatic leader of a band of outlaws who captured Jerusalem and made it their capital. Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argue that this is the oldest, most reliable part of Samuel, and the rest of the David story is without historical basis.

Baruch Halpern argues that David was a vassal of Achish, the king of the Philistine city-state, Gath, and David never ruled an independent kingdom. For Steven McKenzie, David came from wealthy family and was an ambitious and ruthless tyrant who murdered his opponents, including his own sons. Bandit leader, vassal, or wealthy tyrannical murderer -- whichever he really was, most of the Biblical account of David appears to be the creation of an exiled people's deep yearning for a story of past glory.

In the process of constructing that story, a detailed ancestry for David was concocted, going back to Abraham eight or nine centuries before David. While David was, it seems, a real person, albeit not much like the Biblical depiction, Abraham was entirely made up. The creation and telling of these stories gave hope to the Hebrew people in a time of despair and suffering and defeat. The stories told them of a past time of glory and also called them to hospitality rather than to bitterness.

The glory and the hope represented by David needed a foundation -- so fragments of other mythic tales were woven together and expanded into a story of exodus and Moses and covenant, set four hundred years before David. The exodus story established a context that showed that David didn't just happen. David was the long-coming fruition of Moses' covenant four centuries earlier. But Moses didn't just happen either. The promise on Mt. Sinai was itself the long-coming fruition of the foundation laid by Abraham in a narrative arc set another 4 or 5 centuries before Moses. And that foundation was hospitality.

The stories of Abraham, Moses, and David reassured the Israelites that they had a history. Their history, fictional or not, was their basis for hope for a better time to come -- for it told them God had promised to make the descendants of Abraham a great nation. It told them that the path of the fulfillment of that promise was a winding one that had taken them into captivity before, in Egypt. They had emerged from past captivity into a time of freedom and prosperity, and so could again. Without that story, composed in oppression and exile, the Israelites are one more Ancient Near East tribe – along with the Jebusites, Ammonites, Aramites, Midianites, Moabites, Edomites, Huttites, Etceterites. But with that story, the Hebrews coalesced around it into the religion recognizable as Judaism.

Some of the writings of the Babylonian captivity do express deep bitterness, anger, violent hatred of the Babylonian captors. Here, for instance, is Psalm 137:

By the rivers of Babylon -- there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion.The first two of three verses have a plaintive beauty that has made the Psalm a popular one for setting to music -- but the musical versions leave out the deeply vicious ending. If the bitterness of their oppression didn't make the bitterness of their hearts understandable, I would be tempted to call the Psalm unredeemable. In the midst of that bitterness, understandable or not, some of the Hebrew story-tellers had the wisdom and the courage to perceive another way: a way of hospitality rather than bitter and violent anger.

On the willows there we hung up our harps.

For there our captors asked us for songs, and our tormentors asked for mirth, saying "Sing us one of the songs of Zion!"

How could we sing the Lord's song in a foreign land?

If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither!

Let my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth, if I do not remember you, if I do not set Jerusalem above my highest joy.

Remember, O Lord, against the Edomites the day of Jerusalem's fall, how they said, "Tear it down! Tear it down! Down to its foundations!"

O daughter Babylon, you devastator! Happy shall they be who pay you back what you have done to us!

Happy shall they be who take your little ones and dash them against the rock!

Giving vent to pain does not heal the wound; it only expresses the pain. So these story-tellers brought forth from the imaginations of their better selves another sort of story, a salve for smoldering hatred -- a story that called the people not to pay back violence and death, but to pay forward compassion -- a story not of pain that makes more pain, but a story of hospitality that engenders healing and wholeness. That's the story the Israelites in their captivity put into the foundation of the narrative that defines the Jewish people, hence the Christians and Moslems, hence us.

The Abrahamic tradition has not had any easy go of it. Jews, Christians, and Moslems, are still fighting – though modern warfare kills a smaller percent of us than early human warfare did. Religion’s ancient use for war runs deep and is not easily replaced by its new use for peace across tribal lines.

Sometimes people do harmful things in the name of religion – harm their children, harm themselves, blow things up, go to war. That’s because religion hasn’t finished outgrowing and transcending its original tribal function. But it’s getting there.

The Israelite story-tellers, in the midst of their captivity, homelessness, and pain, found a way to remember others’ pain, too. Somehow they found a way to make stories to move their hearts from pain toward compassion, to care for the stranger. What they illustrated in story, they codified in principle, for Deuteronomy was also substantially created in Babylonian captivity:

You shall also love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt. (Deut 10:19)

Swords Into Plowshares

Our early ancestors needed a way to draw out of each other the last full measure of devotion on behalf of the tribe. They needed something that would provide:

- a sense of powerful entities watching and judging, and

- a sense of overflowing love, a joy in the life shared with tribe-mates.

Failure of the capacity for spiritual connection meant death. Today, it means that still – only now, the “tribe” at stake is the planet. In any species, genes won't survive if they don't incline individuals to care adequately for their young. Social apes like us, had also to build in an intense care for our group. We had to even be willing sometimes to set aside our interest in our selves and our own offspring for the sake of something bigger. The groups that did that survived.

The stories that emerged in the Babylonian captivity have not ended the violence that oppresses our planet. Those stories do show us what is possible. The violence can be ended.

Our spiritual hardware is built into us. It's what we have and what we are. It was made as a sword. It's up to us to beat that sword into a plowshare, cultivate fields of care, and sew the nourishing knowledge that we are one. It is up to us to find the ways to connect, to cultivate compassion for enemies, to train ourselves in nonviolence, to recognize that violence is any thought, word, or deed that treats a being like an object or diminishes a being’s sense of value or security.

Thus we stand in the Abrahamic tradition of hope and possibility, stand with the radical vision of some captive Israelite story-tellers.

What they dreamed be ours to do.

Hope their hopes and seal them true.

- - - - - - - - -

Revised version of sermon preached at the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Gainesville, 2011 July 17. For list of all blog posts derived from sermons, click here for Sermon Index.

Audio Podcast of the original sermon: click here.